#somereallygoodones, #henryhorenstein, #balls, #charlesjones,

In appreciation of classical statuary, art historians introduced the idea of contrapposto. It referred to a figure balancing their weight on one leg by shifting out a hip, achieved by seeming to be off balance. Maybe that has happened here. Balls don’t lend themselves to symmetrical …er … handling. (There is a level of anxiety in this discussion that makes everything funny.)

Henry Horenstein. “Untitled”, 1990s

Looking closely, you see two moon scapes; you can probe the surface with its whorls and bumps, small white pimple-like affairs. Much of the pubic hair looks as if it is not coming out of the skin but rather floating around it. Hairs catch the light adding some electricity. There is a dense mass at the top of the frame and the top edge of the image declare a separation from the pelvis, but the tendrils of hair seem like thatching or a mass of dark, heavenly clouds or smoke.

Am I looking at it too closely?

There is also that unexpected cord-like fold or crease running vertically down the center of the frame. Is that holding everything and does it have a name? Because the print is black and white it may be easier to make this examination. Color would make it difficult to sort this out through all those blues and pinks.

The image would appear to have been made on a warm day … . These low hanging fruits, these plump plumb plums, are scandalous, and I cannot think of another image like it.

The good news is that if this photograph has been published in a book there has been a positive change in the conversation about sex. When I did “The Unseen Eye” ten years ago, I wanted to include a close up image of the head of penis, an unusual artist’s self-portrait. It looked like an enormous eyeless face, like a clock with a small, odd slit at six o’clock. A seeming blob of skin filled the frame, but I could not make out what it was. Other people either knew immediately or were bewildered like me. For the book, the image was mocked up on to a page with two very different pictures and the whole thing looked swell, typologies of forms that looked like eyeballs.

If it were to remain, my English publisher insisted he wouldn’t be able to sell the book to the Japanese, and then he told me he hadn’t actually shown it to them. The French had no problem with it. They only had reservations about a Sept 11th photograph of a man falling to certain death.

It was the Americans — Aperture — who said no. This conservative, very American, reflexive refusal to have anything to do with male sex parts has long been baffling and unsettling to me. There is little reluctance to show female figurative work — particularly depilated and aestheticized vulva, you know, Art.

Robert Mapplethorpe opened things up — er, again — for epic and erect penises, but not BALLS.

This is a still life study of two testicles in their scrotal sack. I encountered this image with its female equivalent when judging an American Photography Annual competition. Kathy Ryan, the longtime director of photography at The New York Times Sunday Magazine was the head judge, and she had asked me to join along with another half dozen photo types. We got to spend a day looking at tear sheets and books prints (!). This is worthy of an exclamation point because today judging like this would all happen remotely with digital thumbnails on your computer.

The group was walking between the tables, and we came upon Henry Horenstein’s balls.

Henry Horenstein is a great fellow, beloved in the photo world, a longtime teacher at RISD (Rhode Island School of Design), a filmmaker and author of many books. He has had a full life and career, and he’s a good photographer.

True to some form, most of the jury oohed and awed over the lady part. But I demurred and picked up the scrotum and announced that I would not advocate for the image of a lady’s lap without her mate. People offered up the worst art history appreciation reasons for why the former should stay. The girls’ against the boys’.

I loved the balls, adamantly.

I’d never seen anything like it. I choose to believe that it is a self-portrait and can only begin to imagine the contortions Mr. Horenstein had to manage in making it.

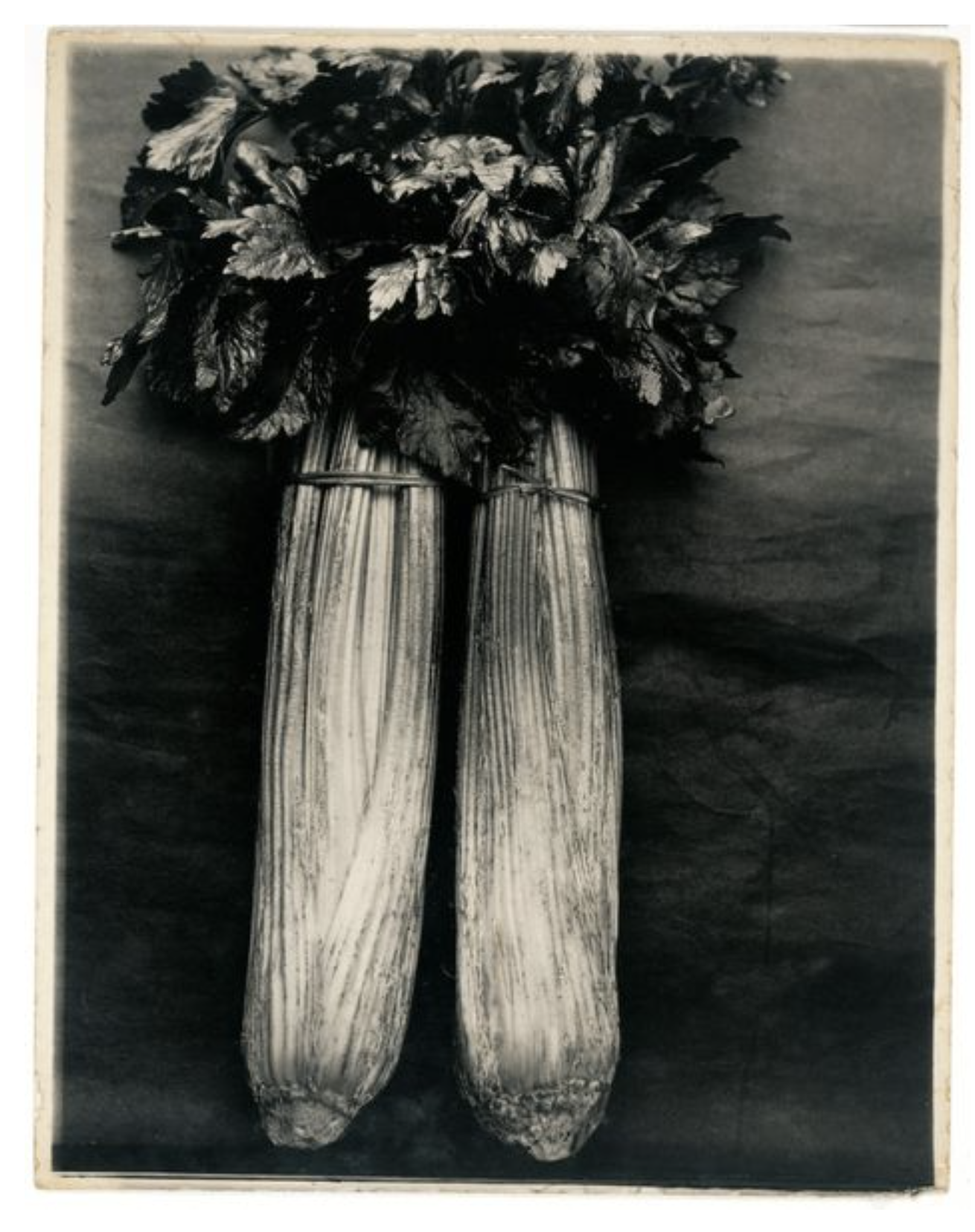

Charles Jones’ “Vegetables, Celery Standard Bearer," late-19th C..

But look at it. Here is the staff/stuff of life. In the history of photography, only the early twentieth century Charles Jones’ vegetable studies compare. It’s difficult to think of another comparable. The pair of pairs make for an outstanding typology.

The Horenstein is hairier. I love the free balling transgression of the photograph. The photographer is throwing down some gauntlet about taste and censorship, and I want him to prevail.

© 2021

#somereallygoodones, #theunseeneye, #wmhunt, #collectiondancingbear, #collectionblindpirate, #greatphotographs, #howilookatphotographs, #photographsfromtheunconsicous, #collectingislikerunningaroundinathunderstormhopingyoullbehitbylightning, #aphotographsogooditmakesyoufartlighting, #photographschangedmylifetheygavemeone, #henryhorenstein, #balls, #charlesjones